Revolutionary Civics: How Should Evanston Spend $3 Million?

The residents of Evanston, Ill. have no shortage of ideas about how to spend a tidy $3 million sum in federal COVID-19 relief funds. Protected bike lanes? Affordable housing? What about revitalizing the downtown area, improving mental health services, or fixing sidewalks?

The residents of Evanston, Ill. have no shortage of ideas about how to spend a tidy $3 million sum in federal COVID-19 relief funds. Protected bike lanes? Affordable housing? What about revitalizing the downtown area, improving mental health services, or fixing sidewalks?

More than 1,200 such suggestions have been made as part of the city’s pilot participatory budgeting program, which lets community members—rather than elected officials—decide how to spend part of the city’s budget.

Ultimately, anyone who lives, works, or studies in Evanston—including teenagers, people who are undocumented, and those who were previously incarcerated— will vote on a final list of proposals. (Register here.) The city is responsible for implementing the winning ideas.

As some people raise concerns about the future of democracy, municipalities across the US and around the world are experimenting with participatory budgeting to increase transparency, strengthen community ties, and restore trust in government. Supporters say it also creates more equitable policies and trains future leaders.

It’s also a lot of work. According to Northwestern researchers, direct democracy demands time, a solid infrastructure, and participation. The process is often misunderstood. More research is needed, meanwhile, to assess whether public budgeting is reaching the traditionally disenfranchised and having the desired long-term effects, such as creating more resilient communities.

“Low participation is one of democracy’s biggest challenges, and people need more opportunities to learn the skills to get involved,” says associate professor of learning sciences Matt Easterday (right), a technical adviser to the City of Evanston. “Participatory budgeting has a huge educational benefit, because it teaches people about policy, government, outreach, community issues, and how to become civic actors.”

“Low participation is one of democracy’s biggest challenges, and people need more opportunities to learn the skills to get involved,” says associate professor of learning sciences Matt Easterday (right), a technical adviser to the City of Evanston. “Participatory budgeting has a huge educational benefit, because it teaches people about policy, government, outreach, community issues, and how to become civic actors.”

First used in Brazil in 1989 to empower working-class and low- income residents, participatory budgeting reached the US in 2009 when Chicago alderman Joe Moore introduced it to allocate $1 million in public funds. It has since spread to more than 3,000 cities, from Budapest to Boston. Both the White House and the World Bank have supported community budgeting practices.

Critics argue that people with more resources and time are the ones who get involved, so it’s easy for the process to be co-opted by small groups on the extremes. Others say that elected officials make more-informed decisions than the people they represent, since that, after all, is their job. Easterday counters that the process allows partisans less influence “because participatory budgeting provides the support for anyone to participate, not just citizens who know how to work the system.”

In Evanston, 51 percent of those attending idea-collection events or expressing opinions to elected officials had never done so before, according to surveys his team conducted. “It’s about as democratic a process as we can currently design,” he says.

It was also never meant to replace the regular budgeting system or the jobs of elected officials. Evanston’s pilot program apportions less than 1 percent of the city’s total annual budget, not including over- head and administrative costs, says city council member Jonathan Nieuwsma, also a member of the council’s participatory budgeting committee.

“It would be ridiculous to ask 78,000 Evanston residents to weigh in directly on every contract for pothole repair, snow- plow purchase, or software upgrade,” Nieuwsma says. “The few people who may feel strongly about those things have channels for input, and I often seek input from constituents with particular expertise in certain areas.

“This is an experiment,” he adds. “Let’s see how it works, what lessons we can learn, and if and how we might be able to build a participatory budgeting component into our regular annual budget process.”

The hidden process of organizing

The planning phase began in late 2021, when the city council approved using American Rescue Plan Act COVID-19 relief funds. It created a steering committee and hired a full-time participatory budgeting manager, a field manager, a part-time coordinator, and advisers from Northwestern.

The Northwestern team, led by Easterday, includes graduate students Kristine Lu, Gus Umbelino, and Morgan Wu and an army of more than 20 volunteers, most of whom are undergraduates pursuing certificates in civic engagement.

They oversee the technical aspects of the entire project—everything from training volunteers on informing the community to running events and designing a system to develop ideas into proposals.

“There’s a hidden process of organizing and advocacy,” says Lu, a newly minted PhD, who has been researching ways to increase civic engagement with Easterday since 2017.

“These things don’t just appear out of the blue. It takes a lot for a city to build up the necessary resources, skills, and motivation to ensure its community members can pull off participatory budgeting.”

Over several months, Evanston held 12 idea-collecting sessions in community centers, restaurants, and other locations, targeting a wide cross section of the public. Volunteers contacted more than 1,000 people face-to-face, reaching 2 percent of Evanston voters, Easterday says, and people also submitted ideas online.

Civics in action

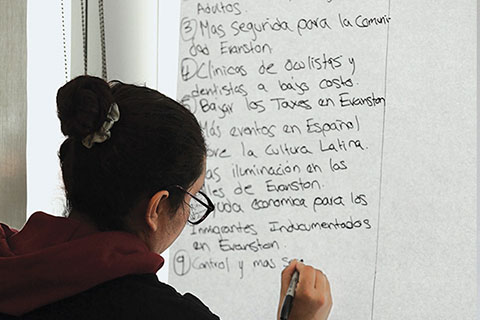

At one brainstorming session, held at Evanston Township High School and organized by high school senior Emmett Ebels-Duggan, teenagers and community members sat four per table, eating free pizza, enthusiastically discussing ideas and writing their favorites on an easel pad.

At one brainstorming session, held at Evanston Township High School and organized by high school senior Emmett Ebels-Duggan, teenagers and community members sat four per table, eating free pizza, enthusiastically discussing ideas and writing their favorites on an easel pad.

Some students came because they were civic-minded, says Ebels-Duggan, a member of the steering committee. Others were simply committed to a certain idea, such as installing table-tennis tables around the city. “It showed that people with one or two ideas who have no further involvement can be part of participatory budgeting,” he says.

Students also tried to solve problems that adults may not be aware of. Senior Amira Grace wanted to improve a “shortcut”— a rough path that many use to walk to school. Ebels-Duggan, a competitive cyclist, liked the idea; he also supported a two-way, curb-protected bike lane to be built down the length of a major northsouth thoroughfare.

For more than an hour the ideas kept pouring in: What about a program that connects seniors to young people? Dedicated pickleball courts? Or turning the abandoned Harley Clarke mansion into a community center?

“What’s been rewarding and surprising is, when it hits right and you see people engaged in the process, how excited and hopeful they are,” Lu says. “At the core, civics is not just about voting and learning the three branches of government. It’s about building relationships with other members of the community, talking to people you don’t know, and finding shared interests.”

During the proposal development phase, volunteers fleshed out the ideas received, a process shaped by research from Easterday’s team and interviews with community members, policy researchers, and others. The final vote, which will likely include between 14 and 26 proposals, is scheduled for fall 2023.

"We’ve really gone into this unexplored space of training students how to do things like canvassing and getting people excited to come to civic events,” says Lu, whose dissertation explored the paradox of participatory democracy. “As wonderful as democracy is, it requires people having the ability to participate in it. And that’s not a given.”