Capstone Spotlight: Designing Difficulty - How Managers Can Stretch Talent with Intention

At Northwestern’s Master’s in Learning and Organizational Change (MSLOC), our students don’t just study how organizations work — they learn to change them. The capstone project is a powerful expression of this philosophy: learners apply research, design, and leadership frameworks to real-world challenges to deliver actionable insight and impact. We’re excited to launch our Capstone Spotlight blog series and share how MSLOC students translate theory into practice and shape the future of thoughtful, human-centered leadership.

In our first featured project, current MSLOC student, Douglas Dinwoodie, tackles one of the most pervasive yet overlooked questions in management: How do we stretch people without breaking them? Through research, reflection, and a new model for intentional challenge, this capstone shows just how deeply the MSLOC curriculum prepares leaders to think systemically, lead with empathy, and design for growth.

As Douglas puts it, “For me, Northwestern’s MSLOC program was about weaving the small things into a greater whole — lifting details into strategy, and turning unfocused awareness into purposeful action. Through my Capstone experience, I found the language and evidence to bring intuition to life, creating change through mindful, human-centered leadership.”

Plan Before You Push: Calibrating Challenge with Care

You know the experience. Your inbox pings with a new project assignment, and there’s multiple potential reactions. It’s impossible -- there's no way you can do this, but you must. A knot of anxiety begins to form in your stomach. Or perhaps instead you read the email and sigh -- another tedious assignment, another waste of your potential. You feel your motivation melting away.

Neither experience feels great. One breeds quiet despair, the other, quiet boredom. Both lead to sub-par outcomes for you and the organization.

Most managers don’t set out to cause either. They’re trying to match people to projects thoughtfully -- but with limited visibility into each person’s readiness, confidence, and support, it can feel like guesswork. The result: a lot of well-intentioned assignments that miss the mark

Repeatedly seeing talented people either underused or overwhelmed -- and hearing one manager admit, “I thought I was challenging her, but I was actually leaving her alone in the dark” -- led me to explore the question at the heart of my capstone: How can managers design project assignments that stretch people without breaking them?

Why This Problem Matters

Assignments aren’t just about completing projects -- they’re developmental bets. Every project shapes confidence and capability, yet difficulty is rarely examined. Work gets distributed by habit or urgency rather than intent. The result is predictable: some people stagnate, others flounder, and both waste potential.

In my own work leading cross-functional teams, I repeatedly saw managers trying to be fair and efficient, but without a reliable way to gauge how much challenge is too much.

This project drew on quantitative and qualitative data from managers who assign projects, grounded in two core research ideas. The first is desirable difficulty (Bjork & Bjork, 2011) -- the principle that learning happens best when tasks are effortful but achievable. The second is psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999) -- the belief that people learn and take risks when they feel supported rather than judged. Together they reinforce a simple truth: challenge works when it’s intentional and supported.

The Diamond Model of Difficulty

For my capstone research, I received 42 survey respondents and completed 9 in-depth interviews. I found that most already consider skill fit when assigning projects -- how well a person’s abilities match the work’s demands. They are often trying to get this part right, but focusing only on skill fit means missing the other forces that make stretch work succeed or fail: ambiguity, pressure, and support.

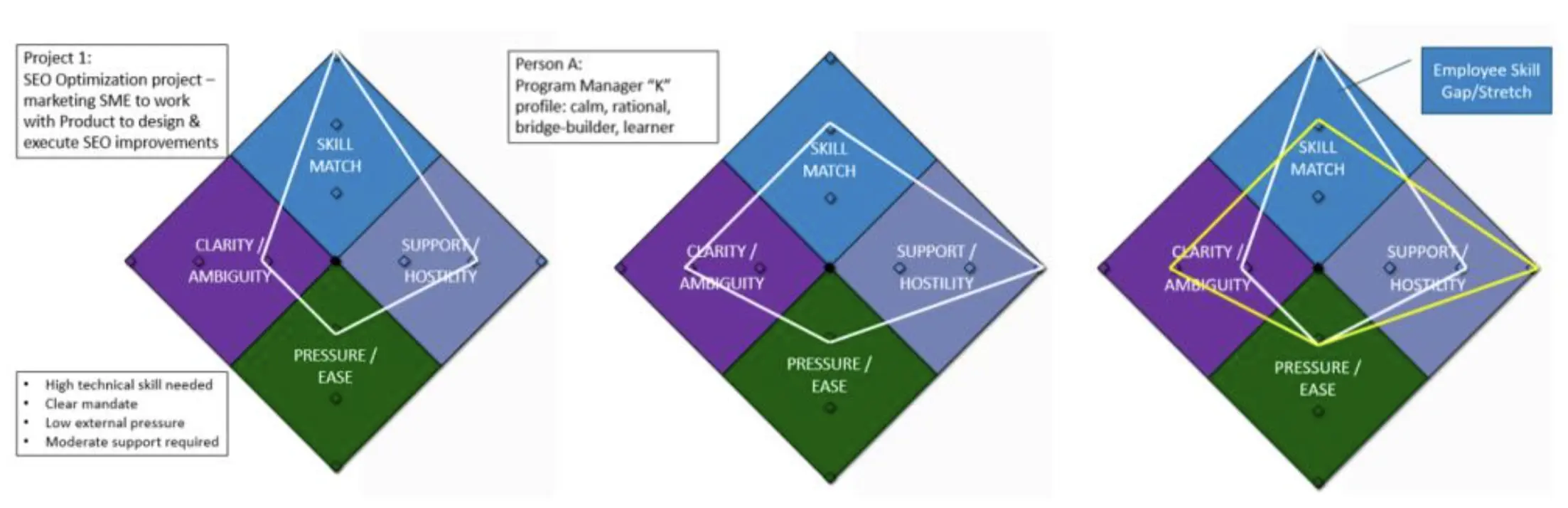

To make those dimensions visible and usable, I developed the Diamond Model of Difficulty -- a framework to visualize challenge across four factors:

- Skill Fit – alignment between ability and task demands

- Ambiguity – how clear the path is, or how much must be invented

- Pressure – visibility, stakes, and scrutiny

- Support – scaffolding from peers, leaders, or tools

Think of these as gauges on a dashboard. A project can be high-pressure but well supported, or moderately ambiguous with strong skill fit. The individual can be mapped the same way – think of their skill level and self-reliance, consider their tolerance for ambiguity and pressure. You can map each dimension as low, medium. Overlaying the two reveals where challenge and readiness diverge.

A perfect match isn’t necessary; the goal is to understand stretch potential and where adjustments can narrow the gaps. If skill fit is low but the project is clear and well supported, it may be a perfect stretch. The aim isn’t to eliminate difficulty but to tune it.

Hidden Forces Managers Often Miss

Ambiguity can derail strong performers. A project that looks straightforward may require inventing the plan or navigating unclear expectations. One manager said, “If an assignment isn’t fully clear, I assign it to someone who is patient and capable of solving deeper problems.” When ambiguity is high, tolerance for uncertainty matters as much as expertise.

Pressure reshapes difficulty. The same task changes under executive scrutiny or client visibility. As one leader told me, “I sometimes give simpler projects to high performers because of the client visibility.” The work wasn’t hard -- the stakes were. Knowing how visibility magnifies challenge helps managers add communication or cover.

Support turns stretch into success. Even when help seems available, people may hesitate to ask. As one manager reflected, “Explicit, regular feedback and support are vital components of my approach to assigning challenging tasks.” Without that scaffolding, psychological safety collapses and desirable difficulty becomes destructive difficulty.

The Diamond Model isn’t the only tool, but it prompts deliberate thought. Managers don’t need a complex process; they need a pause. A brief check across these dimensions builds intent into everyday assignments without adding bureaucracy.

Three Takeaways for Practice

- Plan Before You Push

Pause before assigning. Use the four factors -- Skill Fit, Ambiguity, Pressure, and Support -- as quick gauges. - Stretch with Safety

Psychological safety isn’t about lowering the bar; it’s about building the ladder. Make help-seeking expected and normalize coaching during hard work. - Talk About the Why

Name the developmental purpose. When intent is transparent, even tough projects feel fair -- and success or struggle alike becomes learning.

Growth by Design

Getting difficulty right benefits everyone. Employees feel trusted and supported. Managers grow more confident assigning stretch work. Organizations build capability intentionally instead of accidentally.

The call to action is simple: plan before you push. Treat challenge as a strategic lever, not an afterthought. By calibrating assignments with care -- balancing skill, ambiguity, pressure, and support -- managers can turn everyday projects into engines of growth.

When difficulty is designed, not guessed, stretch stops being a gamble and starts becoming a practice.

References

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher et al. (Eds.), Psychology and the Real World (pp. 56–64). Worth.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.