A Complex Legacy: 70 Years Since Brown v. Board

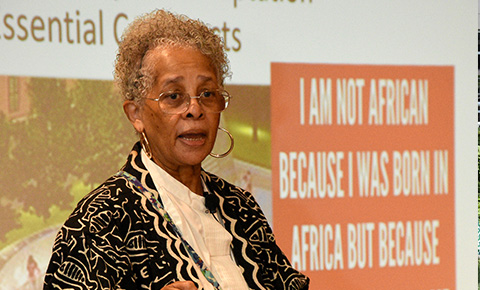

Seventy years after the Supreme Court found segregated schools unconstitutional, it’s clear that simply allowing Black children to sit next to white kids in public schools isn’t enough, School of Education and Social Policy Professor Emerita Carol Lee said during a Northwestern University event exploring the complex outcomes around the landmark verdict.

“The goal now is to create equitable systems and harness the opportunities of public education, no matter who is seated in a classroom next to whom,” said Lee, who urged the audience to take a wider view on the ruling to understand how to move forward.

“With a 400-year history of segregation, expecting change after just 70 years doesn’t take in the complexities of the past,” she said.

Lee’s assessment of the impact of Brown on education policy and practice, which also featured School of Education and Social Policy Dean Bryan Brayboy, was part of a two-day series of seminars and professional development workshops hosted by the School of Education and Social Policy and the Pritzker School of Law, marking the 70th anniversary of the decision.

Held at Evanston Township High School and the Orrington Hotel in Evanston, the event brought together scholars, students, educators, legal experts and Evanston community members for candid conversations around the purpose of education.

In 1954 when Brown was decided, many Black families felt optimistic. Others were skeptical, wondering how it would actually look in practice. As the years passed, both responses turned out to have merit.

Four generations later, many of the country’s schools are even more split across racial lines. And while the country is now more ethnically and racially diverse, the policies that resulted from the ruling – be it bussing Black students to far away schools or offering tracked classes – have also had mixed outcomes.

Today, educators and researchers are still grappling with the aftermath and the overall influence of Brown v. Board as it relates to providing educational equity.

“Our goal is not only to understand the impact of Brown vs. Board of Education as a historical event, but also to forge a path forward,” Nichole Pinkard, the Alice Hamilton Professor of Learning Sciences told attendees. “We are not just commemorating a legal milestone.”

‘Have we really moved on?’

For several faculty members, the Brown decision played a major role in their lives. Political scientist Sally Nuamah, associate professor of human development and social policy, recalled attending a mostly white middle school on Chicago’s North side in the 1990s.

As one of the only Black students, she was assigned to an English as a Second Language class – even though English was her first language. Looking back, it affected her "self-worth and deservingness” as she continued her education, Nuamah said during a round table discussion called “Have We Really Moved on From Separate but Equal?”

Another speaker, Marcus Campbell, discussed how attending predominantly Black schools gave him a stronger sense of self. “My experience in a segregated environment was good,” said Campbell, now superintendent of Evanston Township High School District 202. “Normalizing achievement as a Black kid was just how I grew up.”

Evanston community members also weighed in on the local influence of Brown. Gilo Kwese Logan, an equity and inclusion consultant and fifth generation Evanston resident, says the 1967 closing of Foster School in Evanston’s historically Black Fifth Ward set off a string of difficult events.

While praised as the first suburban district to integrate its schools, Evanston’s approach of bussing Black children to mostly white schools took away from the close-knit communities that formed over generations.

“On one block children attended four different elementary schools,” adding that local stores—including his family’s—also shut down. “When we lost these pillars of our community we lost portions of our village.” (A new school in Evanston’s Fifth Ward is scheduled to open in 2026.)

‘The two trajectories of Brown’

Even as participants look back on Brown v. Board, many other Civil Rights-era protections are now in question, Pritzker School of Law Dean Hari Osofsky, added during a discussion assessing the legal influence of the decision. “There are so many rollbacks in Civil Rights protections,” Osofsky told the audience. “Having legal protections of equity is important.”

Paul Gowder, associate dean of research and intellectual life at Pritzker, pointed to the “two histories and two trajectories of Brown” that have evolved since the ruling.

Most recently, the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard case in 2003 struck down race-based affirmative action in college admissions and pointed to Brown. And a 2007 case that also invoked Brown, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, found it unconstitutional to use race as a factor for assigning students to schools.

On one side, the Brown v. Board precedent gets used in the courts to say that “taking race into account is a form of discriminating by race” while on the other it says that “people of color are entitled to be included in educational institutions as citizens,” Gowder explained. In his view, acknowledging racial inequities is more compatible with Brown.

A path forward

Another participant, LaToya Baldwin-Clark, professor at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, pointed out how a change in funding may be required for this kind of equitable education. Today’s public schools depend on local tax dollars, deepening inequities between schools in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, said Baldwin-Clark. For parents without the economic means, the cycle of being left out of neighborhoods with well-funded schools continues.

“It allows private taxpayers to control the most basic aspect of schooling – exactly the process that Brown was meant to interrupt,” she added.

Many attendees also encouraged a deeper understanding of the intention of schools beyond just learning the basics. Academic success often stems from feelings of safety and belonging in the classroom.

“There is a big takeaway here about what functions the schools serve,” said School of Education and Social Policy Dean Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, the Carlos Montezuma Professor. “Obviously, in some ways we are preparing children for the world they are going to live in, but it’s also about the future of community.”

Related coverage:

- Panel discusses pros and cons 70 years after Brown v. Board of Ed, Evanston RoundTable

- Panel discusses 70 year Brown v. Board legacy in present-day education, The Daily Northwestern