Here's What Creating Change Can Look Like

The chance to walk across the stage at his high school graduation last year was meant to be a triumph for then-17-year-old Nimkii Curley.

But because he was wearing symbols of his Ojibwe and Navajo culture – a sash with traditional floral designs, a beaded cap, a traditional necklace and a single eagle feather, all gifts from community elders and family – he was pulled out of the procession at Evanston Township High School and told that, unless he took them off, he couldn’t participate.

Curley is the grandson and nephew of boarding school survivors. Designed to strip Native peoples of their culture, language, and identity, the schools were brutal places and rife with social, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. That afternoon at graduation, Curley refused to give up the sash and other items. To him, the items were sacred and wearing them was a signal of resistance in a moment that illuminated how little had changed, and how much work needed to be done.

In the months since, Curley, his family and the Native American community have come together to create and lobby for two bills that aim to bolster instruction on Native American history, sovereignty, and present-day issues. Expected to be signed soon by Gov. J.B. Pritzker, the bills require K-12 schools in Illinois to teach Native American history, add a seat for a Native American on the equity commission of the Illinois State Board of Education, and protect the rights of students to wear items of cultural or religious significance.

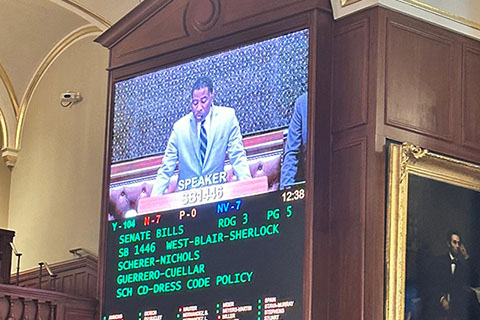

Nimkii Curley traveled to Springfield to advocate for the bills, his sister, Miigis Curley, 14, collected 15,000 signatures on a petition in support, and his mother, Megan Bang, the director of Northwestern’s Center for Native American and Indigenous Research and a professor at the School of Education and Social Policy (SESP), gave expert testimony and helped draft the legislation.

“What was beautiful about my kids’ reaction was they didn’t just want to protect their own rights. The bills protect the rights of all children to express their cultural and racial identity,” Bang said. “Being able to graduate with these cultural items is not just about decoration. It’s a very powerful act of cultural resistance and survival in the face of the genocide that was inflicted upon Native people.”

Nimkii Curley ended up watching his graduation from the audience that day – a fact for which Evanston high school officials later apologized. But Bang says the situation reflects a lack of education in schools, even in progressive places like Evanston. “My son knew the people who pulled him out of line,” Bang said. “He told me, ‘Mom, these are good people. They didn’t realize what they were asking me to do.’ They kept telling him that ‘these things’ [the sash, cap, necklace and feather] weren’t that important.”

At the time of the incident, an effort to draft legislation that would increase the amount of Native American history taught in Illinois schools was already underway. Nimkii Curley’s experience raised public awareness and – with a flurry of news coverage – added a sense of urgency.

A large body of research has shown that culturally centered educational approaches produce better outcomes. But too few school districts have adjusted their policies, Bang said. When it comes to Native American history, only fifty percent of states have some requirement, she said, and most of those standards require teaching about Native people in the pre-1900 period and omit the modern lives and experiences of Native communities.

“Our school systems teach people to think about Native people in ways that are stereotypical and woefully out of date,” Bang said.

Once signed, the laws will require schools to begin teaching the units in the 2024-25 academic year. Schools will be able to structure their own curriculum, and the Illinois State Board of Education will offer learning materials and guidance created with the assistance of Native American leaders and community members.

Once signed, the laws will require schools to begin teaching the units in the 2024-25 academic year. Schools will be able to structure their own curriculum, and the Illinois State Board of Education will offer learning materials and guidance created with the assistance of Native American leaders and community members.

“The history of our state is intertwined with the history of the Native American community. The terms ‘Illinois’ and ‘Chicago’ come from the language of Native Americans,” said Rep. Maurice West, D-Rockford, chief sponsor of the House bill. “In order for us to move forward as a state, we need to know where we can from. The House bill will help our students know the good, bad and ugly about our state – especially Native American history.”

The legislation requires schools to discuss the genocide inflicted on Native Americans as part of instruction on the Holocaust and to also cover the federal relocation programs that in the 1950s moved Native communities from rural areas into cities, including Chicago. Today, Illinois is home to 280,000 Native American people who represent 150 tribes. That diversity is the result of the decimation of Native people and the later relocation programs.

“We live in an urban environment. There are many Native people here representing so many tribes, and our rezes are located elsewhere – all because of termination and relocation,” said Andrew Johnson, a board member of the Chicago American Indian Community Collaborative and the executive director of the Native American Chamber of Commerce of Illinois. “That’s the kind of experience we want to people to understand.”

Bang is involved with creating curriculum guides and other supports for school districts. “Teachers can't effectively teach about things they never learned, were never required to learn to become educators, or have never had professional development on. Leaders can't support their teachers if they don't know either,” Bang said.

Though the family was shocked by their experience, they are pleased with the legislation and are proud of Nimkii Curley.

“He stood up for himself. And then he engaged in a legislative process to make change for everyone,” Bang recalled. “He said at one point, ‘It was terrible that we had to do this but I’m glad we made it better for those coming after me.’"