70 YEARS ON

The evolving legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education decision

By Alina Dizik

Between bites of TV dinners and plenty of rock ‘n’ roll, American families in the 1950s learned that their lives would be changing in a more profound way: School segregation was unconstitutional.

In 1954 Brown v. Board of Education went before the Supreme Court, which ruled that state-sanctioned segregation violated the 14th Amendment. Like other landmark cases, the decision rippled across the nation.

Many policies stemming from Brown took decades to implement. Even today, the milestone of the civil rights movement has a troubled legacy and continues to affect educational equity around the country.

A controversial decision by the Evanston/Skokie School District 65 school board to build a new school in the historically Black part of the city—to replace one closed in the 1960s— is seen by proponents as an attempt to remediate past harm.

Last spring, SESP, with Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, marked the 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision with a two-day series of seminars and workshops. Three members of our community who participated in the event talk about how they were directly affected by the decision.

Disconnected communities

Nichole Pinkard, Alice Hamilton Professor of Learning Sciences

What she studies: Connecting educational opportunities across homes, schools, neighborhoods, and communities.

Pinkard was a high school senior in Kansas City, Kansas when she visited Northwestern as part of a summer leader- ship program. To broaden their experience, the group of students spent a day with public school students from Chicago’s West Side. Afterward Pinkard’s group was asked to reflect on the differences in opportunity they observed in Chicago compared to their own school.

“The inequity of our out-of-school opportunities gnawed at me,” says Pinkard, who began thinking about how supportive and connected communities can change lives. She attended Stanford University and later returned to Northwestern to keep studying the issue, becoming one of the first people to earn a doctorate in learning sciences.

Today her research in digital learning opportunities for urban youth drives her career.

But she has mixed feelings about the Brown legacy, which left scars and tensions in many communities, including her own.

Many Black boys ended up dropping out after Kansas City opened a new magnet school in 1979 as a response to school desegregation, she says. In her own case, Pinkard thought she’d be attending the neighborhood school with friends. Instead she rode a bus for 52 blocks to a new high school.

“Every block that took me closer to educational opportunities took me further away from community bonds and friendships I’d developed from birth,” she says. “The disconnect that grew in my community became the connection to the rest of my life.”

Embracing new neighbors

Paul Goren, director of the Center for Education Efficacy, Excellence, and Equity

The center’s mission: To address educational inequities and improve K–12 education by providing school districts with timely, rigorous analyses of student progress.

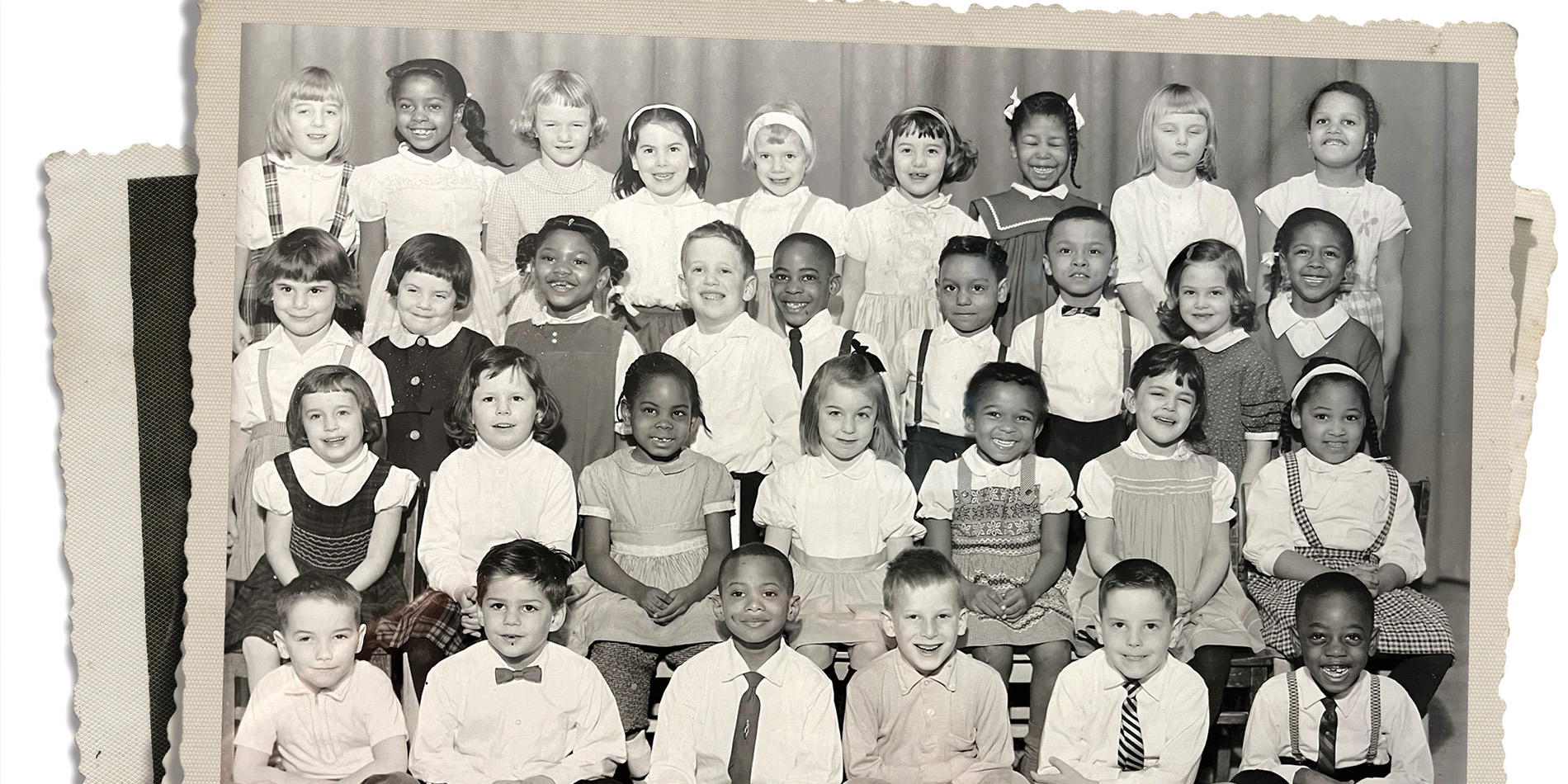

A 1968 class photo on the wall of Goren’s office in Annenberg Hall offers a striking glimpse into his formative years. In it, he’s sitting cross-legged in the first row, wearing a tie, and smiling broadly. Goren is white; his classmates at Chicago’s Avalon Park Elementary School, also dressed formally and grinning, are nearly all Black.

Goren still remembers when the first Black family moved into his South Side Chicago neighborhood in the early ’60s.

There was no official welcome, but neighbors noticed. Some white families began to grumble, and a few moved away. Goren’s parents, both white, had moved into their home in 1958 and lived there for nearly six decades, ignoring calls from real estate agents. His school years felt carefree and safe.

“We all played wiffle ball in the backyard and rode our bikes in the park, yet all around me the white families were rapidly leaving,” he says.

Goren began a career in public schools after attending Williams College and later earning a doctorate in education from Stanford University. He raised his family in Evanston and sent his three children to Evanston/Skokie School District 65’s public schools.

Later, as superintendent of the district in 2014, he commissioned an equity audit of every building, created an equity statement and policy, moved the curriculum to embrace culturally relevant practices, and, after recognizing that a disproportionate percentage of students of color were being disciplined and suspended, shifted the district toward more restorative practices.

In 2021 Goren joined SESP, where he founded the Center for Education Efficacy, Excellence, and Equity research practice partnership.

“My work over the years to improve urban schools was a result of living through an era of white flight,” he says. “From my perch, there was nothing wrong with the schools, but rather with the adults who would not embrace integrated school environments.”

Hope in learning

Paula K. Hooper, assistant professor of instruction in education and learning sciences

What she studies: How to help educators approach learning as a cultural process and use technology to support inclusive teaching

Hooper’s parents moved to the liberal community of Shaker Heights, Ohio, so their three children could access quality education in the city’s schools. When the district began the integration process in 1970, the Hoopers volunteered to bus Paula, who went with 30 other Black children to a predominantly white school in the wealthiest part of town.

White children, meanwhile, were bussed to the predominantly Black school. Paula’s father, a foreman at the post office, served on the citizens council that devised the voluntary bussing program.

Her mother was a teacher in Cleveland Public Schools; during spring breaks, Paula would join her mother’s class, working with children and setting up lessons. “Education was a big deal in our family,” Hooper says.

But for Hooper, integration was “both heaven and hell.” While many of the Black teachers who transferred to Hooper’s new elementary school were incredibly supportive, it was difficult to find a sense of belonging. When Hooper once asked what she could do to move into the highest math group, a white teacher dismissed the question.

At the time, it left her with a feeling she couldn’t quite name. Now she calls it racism.

Still, the experience fueled her desire to teach in ways that help children believe their ideas and backgrounds are valued in the classroom. When she returned to Shaker Heights as a second-grade teacher, Hooper designed the kind of environment that she had longed for, one that helps all students find their strengths as learners.

“It was a turning point in my commitment,” she says. “Good teaching includes listening to how students talk and think. It is about validating their ideas in the classroom as well as recognizing family, community, and cultural practices in the learning process.

“If we go back to what Brown was really trying to say, we will keep pushing the new ideas and tools for learning and embrace the myriad ways of thinking that all children bring to classroom.”